Alien (1979) is my favorite horror movie, and I’m not alone; according to IMDb, this sci-fi classic appears on lists of the best films of all time and has been selected as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress. Why is Alien so compelling? It appeared post-Star Wars (1977) at a key moment in the history of American genre film, and, as David McIntee points out in Beautiful Monsters: The Unofficial and Unauthorized Guide to the Alien and Predator Films, it recombines the DNA of many science fiction narratives of yore. But since film is, above all, a visual medium, it’s the look of this movie that makes it iconic, including the appearance of the unforgettable Alien herself. These visuals create a palpable world that brings Alien to a level beyond plot or dialogue.

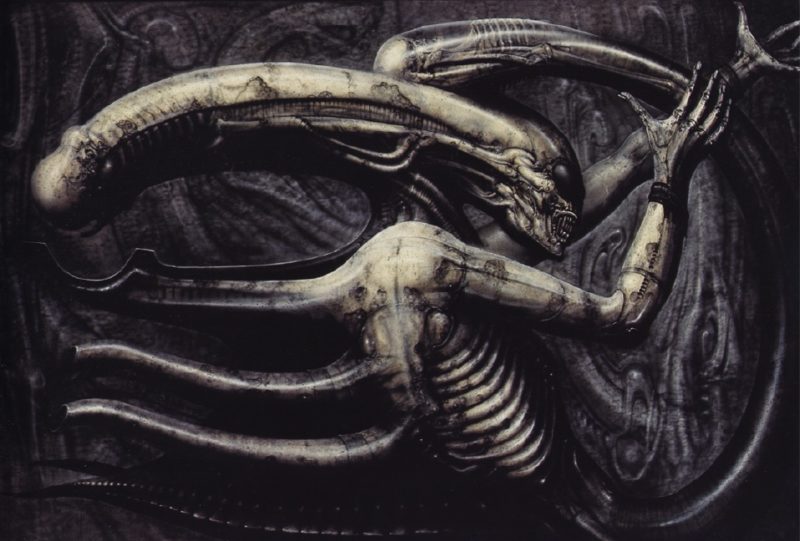

This graphic presentation was the result of a serendipitous meeting: As recounted by Paul Scanlon and Michael Gross in The Book of Alien, writer Dan O’Bannon (who worked on the original script with Ronald Shusett) had been involved with Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune adaptation in 1975. Although that project was never completed, it brought together O’Bannon and three great fantastic artists: H.R. Giger, Moebius (Jean Giraud), and Chris Foss, known for their work in painting, comics, and science fiction novel covers respectively.

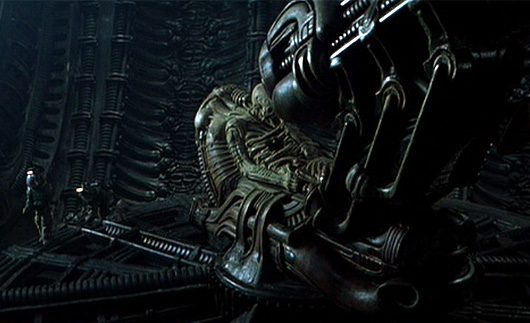

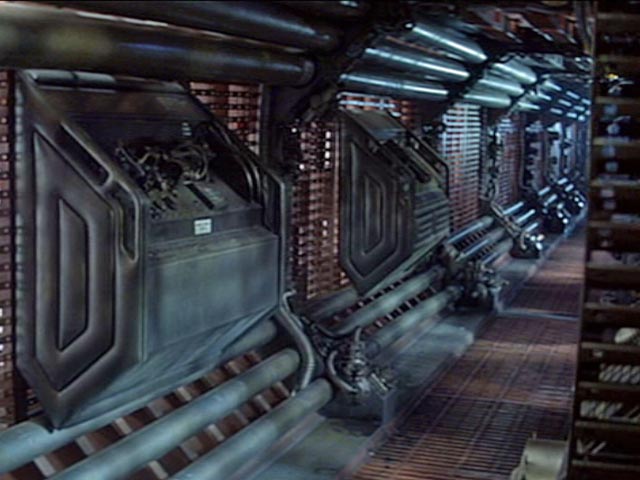

We can divide the look of Alien into two main contrasting yet overlapping realms. According to Scanlon and Gross, director Ridley Scott, Foss and the illustrator Ron Cobb (who had also worked on Star Wars) designed the gritty, military-industrial look of the ship’s interiors, which contrasted with the inside of the darkly biological alien vessel. Designed by Giger, this is where the crew encounters the Alien’s eggs and the facehugger.

One of the most striking things about the ship, Nostromo, is its lived-in, blue-collar look. We see workspaces with coffee cups and masking tape patching up tears in a seat, pornographic pictures and magazines that have been hung up or left lying around, and the crewmembers smoking, their clothing rumpled. This look fits the natural dialogue of the crew, which initially focuses on such practicalities as their pay. Anticipating the cyberpunk movement—keep in mind that Ridley Scott went on to direct Blade Runner—Alien’s visuals portray a future not glamorous and adventure-filled, but rather characterized by banal, dangerous labor directed by distant capitalist interests.

The film’s most iconic element, the Alien itself, was also Giger’s brainchild. The creature’s design was based on his painting, Necronom IV, from his collection, Necronomicon. The Alien costume included bone and car parts, as much a cyborg fusion of organic material and machine as it appears to be. The inside of the crashed ship that the crew explores shows the characteristic dark, biomechanical womb imagery of Giger’s art, expounding upon the artist’s preoccupation with the fusion of birth and death.

These contrasting yet interpenetrating human and alien interior realms gesture toward an anxiety concerning the multinational capitalism that the Company (AKA Weylan-Yutani) represents, birthing uncanny fusions of machine and biology ultimately detrimental to human survival, like the robotic Science Officer Ash (Ian Holm) and the Alien itself. That this film reveals its deeper concerns so beautifully through the design of its visual world is the reason that I find it unforgettable, and accounts for its enduring appeal.

PopHorror Let's Get Scared

PopHorror Let's Get Scared