The misunderstood monster is a theme storytellers have been fascinated with for generations. From Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, these stories have often brought to light mankind’s tendency to quickly judge the unknown and have gifted us valuable lessons on perception versus reality.

As this October 10th marks the 40th anniversary of David Lynch’s masterpiece, The Elephant Man, I’ve taken the time to reflect on the threads that bind the film to this narrative’s history. While it is more drama than horror, Lynch still utilizes a lot of horror’s most prominent themes and stylistic traditions. This is not the story of a monster; it’s instead the story of a man who was treated like one, and its ultimate message of empathy and compassion is one we need to be reminded of now more than ever.

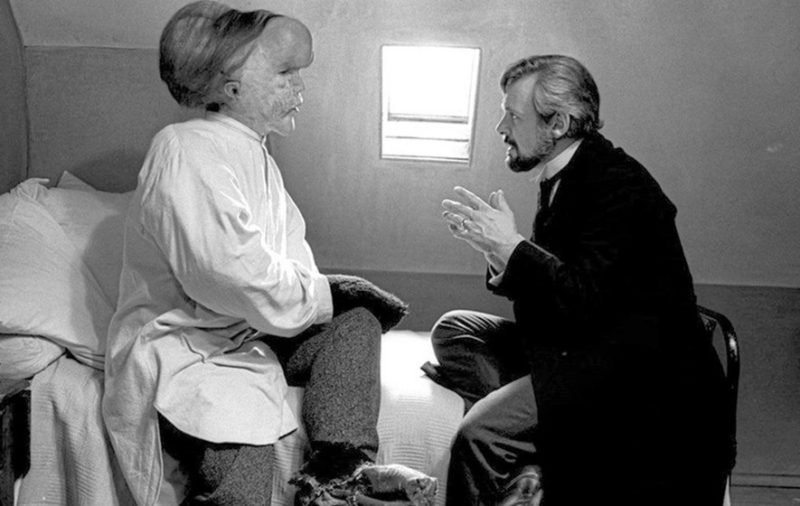

The Elephant Man is based on the true-life story of Joseph Merrick, a man who lived in the late 1800s and was largely known for the rare condition which caused a majority of his body to be covered in tumors and deformities. In the film, he is initially known as The Elephant Man, a crude nickname given to him by a cruel carnival barker named Mr. Bytes, who claims to own Merrick (John Hurt: Alien 1979). While their sideshow is stationed in London, a doctor by the name of Frederick Teves (Anthony Hopkins: The Silence of the Lambs 1991) happens to attend. As a doctor of anatomy, Treves is instantly fascinated by Merrick’s condition, and pays off Bytes to meet with him privately. Upon inspecting Merrick, Treves realizes he’s being regularly flogged by Bytes, and arranges for him to be admitted to the hospital in London. Treves does this in order to study Merrick’s affliction further, while also saving him from more abuse at the hands of Bytes.

During his time with Merrick, Treves begins to slowly develop a trusting relationship with him. With time, Merrick opens up to his new friend and expresses an interest in learning more about the outside world. He tells Treves his life story and explains the constant struggle he suffers due to his illness. The doctor begins to introduce Merrick to affluent citizens and even his own family. Merrick is overwhelmed with the newfound sense of love in his life and is grateful for all that Treves has done for him. All appears to be going well until the wicked Bytes returns—bitter about his “property” being stolen away from him and desperate for some income. In a series of devastating events, Merrick is kidnapped by Bytes, who returns to showing him off in a sideshow. Thankfully, Merrick is not held prisoner for long before escaping and finding his way back to Treves, who takes him in at the hospital once more on a permanent basis.

Upon revisiting The Elephant Man, I was instantly struck by its aesthetic and how stylistically Lynch drew influence from studio monster films of the 1930s. Shot in black and white and utilizing minimal camera movement, the film appears as if it were made in the 1930s which feels like a deliberate homage to filmmakers such as Tod Browning and James Whale. You can easily connect The Elephant Man to films like Freaks and Bride of Frankenstein.

These are stories about outcasts—those deemed unfit for “normal” society. This social caste system extends far beyond the halls of our high schools. For centuries, we have lived in a world obsessed with appearances, and those who are deemed abnormal are pushed to the fringes of our society. Like Browning and Whale before him, Lynch is more interested in a sympathetic portrayal of the outcast, and this is expressed through Merrick’s lone motive throughout the film: to have a friend. This is directly aligned with Whale’s depiction of The Monster in Bride of Frankenstein, especially when examining the iconic scene between The Monster and the old blind man, who has no way of knowing how The Monster appears, and so he welcomes him into his home. This classic example of compassion acts as the blueprint for Lynch’s telling of Merrick’s story and helps inform The Elephant Man‘s core themes.

Of course Merrick does find a friend in Treves, who is at first unsure of his own intentions in helping Merrick. Treves questions whether or not he has truly made Merrick’s life better or just put him on display once more for a different crowd of people. Treves is vindicated in the end when he clearly prioritizes Merrick’s wellbeing over everything else in the film’s final act. Treves fights for Merrick’s permanent residency in the hospital and gives him one last gift of attending a proper theatrical performance, which Merrick appreciates greatly.

Before the performance, Merrick tells Treves the difference he has made to his life and how grateful he is to finally have a friend. The doctor expresses that he’s been humbled in his time knowing Merrick and has learned a lot from him, including the worth of compassion, understanding, and love. He’s learned that appearances are only just that and have no value in determining the true character of a person. Lynch is more careful to draw attention to the real monsters of this story: Mr. Bytes, Jim, and his crowd of drunks. These are the true villains—those who appear “normal” on the outside while being despicable wretches on the inside.

In The Elephant Man’s darker moments, Lynch pulls no punches. These are some of the most difficult scenes I’ve ever watched in a film and made revisiting the movie a bit of a personal challenge for me. As someone who has never felt included or like I belonged to any popular group of people, I’ve felt a profound connection to Merrick’s story.

Prior to revisiting the film for this review, I hadn’t watched The Elephant Man since the very first time I saw it many years ago. It’s not a particularly fun film to watch—and yet I was relieved to find more positivity and optimism in the film this time around. Lynch is forever determined to see the good in our world, and he is quick to remind us that for every villain that exists, there is also a Treves to counteract them. As long as we choose compassion over fear and attempt to understand what is unfamiliar to us, light will outshine the darkness.

The Elephant Man touches something deep within me because its message rings so true to me and so many others. We all just want to fit in—we want to belong. We want a sense of purpose and meaning, and we want to feel loved. When we strip back all of the superficial elements of our world, we’re all just looking for a friend, just like Joseph Merrick. The film’s message seems especially relevant now in a time when fear and hatred have reared their ugly heads again. Elephant Man is possibly Lynch’s most accessible film and also potentially his best. It holds up so strongly and retains all of the emotional power it held in its day. By taking cues from the likes of Mary Shelley, Lynch has crafted a similar story told with kindness and an open mind, guiding us and challenging us to live our lives by its example.

PopHorror Let's Get Scared

PopHorror Let's Get Scared