There’s a game that Bruce Campbell likes to play at convention appearances, a sort of a Hollywood Red Light, Green Light. He picks some poor sap in the audience to play a Paramount Pictures executive tasked with deciding whether or not to make a movie with some of Hollywood’s finest talent. He lists a novel from Michael Crichton, author of then-recent thermonuclear hit Jurassic Park, adapted to a screenplay by Academy Award-winning screenwriter John Patrick Shanley. On board are Steven Spielberg’s veteran producers, Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy, E.T. cinematographer Allen Daviau behind the camera, and FX artist Stan Winston (Terminator franchise, Predator franchise, Jurassic Park franchise, Aliens 1986) handling the creature effects. The editor of Lawrence of Arabia, Anne V. Coates, will piece it together with music from legendary composer Jerry Goldsmith.

Now, do you make that deal?

The hapless volunteer, naturally, says yes.

Campbell congratulates them and then regrets to inform them that they’ve just greenlit Congo.

Unfortunately for Congo, the worst thing that could’ve happened to it was 1993’s Jurassic Park, which may not have been the first Crichton adaptation, but it was the first with box office receipts that could be seen from space. The decade following its release saw adaptation after adaptation of his primarily techno-thriller library: Rising Sun (1993), Disclosure (1994), Sphere (1989), The 13th Warrior (1999), Timeline (2003), and 1997’s The Lost World: Jurassic Park (based on the sequel novel Crichton only considered at Spielberg’s personal request). And then, there was Congo.

Congo was Paramount’s best shot at winning the summer of 1995, releasing in the wake of Universal’s Casper, a few days before Disney’s Pocahontas and only a week away from Warner Bros.’s Batman Forever. Congo ended up grossing less worldwide than While You Were Sleeping, a Sunday afternoon TBS staple starring Sandra Bullock that cost about a third as much to make. Variety called it “a Mystery Science Theater 3000 special event.” The action figures, partially assembled from leftover Jurassic Park molds, warmed the pegs of KB Toy Outlets into the new millennium. Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis tie-in games, the former port actually completed, never even made it that far.

The trouble began fifteen years prior, when Crichton wrote the novel out of accidental obligation. He wanted to tell a story already out of style, a lost world story of great white hunters imperiled in exotic jungle hell. Twentieth Century Fox liked his direction enough to buy the film rights before a word of it was written. After much writer’s block and at least one trip through a sensory-deprivation tank, Crichton cleared the $1.5 million bounty on his head and turned Congo into one of the best-selling novels of 1980. He tried to direct an adaptation with Sean Connery courted for the story’s resident Great White Hunter, but he couldn’t find a reliable enough ape to co-star. Neither could John Carpenter, Peter Hyams, or Steven Spielberg. The book, it seemed, was unadaptable.

Though it still had thickets of trademark techno-babble to hack through, mostly about lasers and the future of telecommunications, Congo was overblown pulp from cover to cover, and, as another bestselling writer once said, there’s the rub.

Jurassic Park was Crichton’s Frankenstein, a morality play about the folly of careless creation with enough Monster Mash fun to keep the pages turning. Despite its B-movie trappings, Jurassic Park was an A-story. Spielberg knew it and adapted it as such, thanks in no small part to Crichton’s early drafts of the screenplay.

Congo was originally Crichton’s King Solomon’s Mines, a solid B adventure across the board, but the blockbuster afterglow of Jurassic Park suddenly made it A-picture material.

Jurassic Park also made Congo a lot like Jurassic Park.

A business venture in the middle of a soundstage jungle goes awry. Blood is spilled by beasts unseen. A soulless conglomerate sends somebody out to check on their investment, along with a colorful band of equal-yet-opposite experts who get to know each other on inconvenient flights. The relevant scientists are only wooed into cooperation by the promise of grant money.

Quick, which movie am I talking about?

For the first half hour, the only major change in Congo’s plot is the talking ape. Despite the obvious promise therein, it’s the only square peg in an otherwise charmingly misshapen hole of a movie.

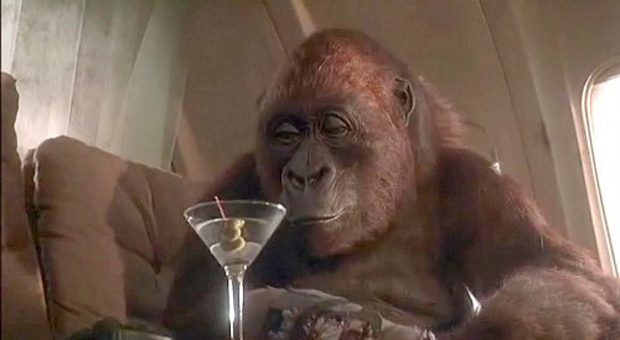

Amy the gorilla, designed as Stan Winston’s challenge for Rick Baker’s monkey suit throne, is still an astonishing achievement 25 years later. She smokes cigars and drinks martinis and bares teeth in protective rage. The first question to cross your mind is how they gave a gorilla vices. The trouble is, she’s simultaneously the spunky Spielbergian kid and Saturday morning comic relief, two profoundly distracting archetypes that threaten to sink any art they’re tethered to. Amy isn’t too far gone on the scale of silly sidekicks, but she’s also an ooey-gooey, tooth-rotting center to a movie that ends in a mass suicide.

Her keeper, primatologist Peter Elliot, doesn’t fare much better. Future Stepfather Dylan Walsh plays him as a bleeding-heart optimist, intending to give up his meal ticket monkey in the hope that she’ll teach her own kind how to use sign language. Not that Walsh is to blame – the character is an Alan Grant surrogate minus any of his prickliness or carefully guarded excitement. Having such a soft hero is an unforgivable sin in any movie that hands Laura Linney a diamond-powered laser cannon.

Fortunately, Congo also took Jurassic Park’s casting to heart and stacked its deck with Teflon-class actors. The aforementioned Linney, Tim Curry, Joe Don Baker, James Karen, Grant Heslov, and Joe Pantoliano, with Delroy Lindo providing the movie’s most memorable line: “Stop eating my sesame cake!” There’s also blinkable cameos from Carpenter-stalwart Peter Jason, a fresh-faced John Hawkes, and Bruce Campbell himself. Sure, there’s no marquee stars, but it’s still an embarrassment of riches when it comes to actors you never get tired of seeing and always deliver, no matter what they’re handed.

I left one cast member’s name out, and that’s because this is Ernie Hudson’s movie. He walks in fashionably late, steals a military transport in five seconds flat, tells the driver very casually to run away, and makes you wonder where he’s been for the first twenty minutes. His character, Captain Monroe Kelly, “Your Great White Hunter for this trip, though I happen to be Black,” deserved his own franchise fighting other Central African cryptids. He calmly endures a plane crash, a hippo attack, a political coup, and a turkey shoot in the dark (borrowed from Aliens and Predator) without ever breaking a sweat. Even his harshest commands are issued with a Transatlantic touch of Cary Grant, and his mercenary glee is never more apparent than when Peter accuses him of being a criminal and Monroe accuses back, “Aren’t we all?”

Congo is at its best when it forgets what it’s trying to be. I’m talking about Monroe skydiving with this ASL-rapping primate wrapped around him like a furry backpack worn the wrong way, Joe Don Baker walking around with a golf club all the time so you know he’s evil, the malevolent Greys announcing their arrival by hurling some poor bastard’s decapitated head like a three-pointer, the climactic showdown where our heroes unload Uzis into an army of mutant monkeys, and the triumphant ending in which said monkeys wipe themselves out by leaping into a lava flow like lemmings in a nature documentary.

Like Campbell’s game, Congo is a movie that is best appreciated in parts, even if they don’t add up the way anybody intended. Shanley, something of an armchair primatologist before ever getting the gig, clearly had his heart set on the Amy plot, but besides giving everybody a flight to Africa, it doesn’t amount to much. The lost civilization of Zinj, a city built and policed by ape slaves bred for ferocity before they revolted and took it for themselves, doesn’t earn much discussion despite the endless questions and implications of its existence. Even Stan Winston’s prized Greys don’t get their due, shot in either smeary slow-motion or unforgiving daylight. They’re chilling in the shadows, when their disfigured skulls glow like prehistoric demons, but Winston was never happy with his work on the movie.

No one decision could’ve turned Congo into a Jurassic Park-sized hit, but there is one that could’ve made it the sum of its mismatched parts.

Bruce Campbell landed his one scene in the movie after narrowly losing out on playing Peter Elliot. I’m not just saying this because this site has “horror” in its name, but had they gone with Campbell, a man who knows exactly how to sell popcorn, Congo would at least have the lead it deserves, square jaw and all. Last time I saw him at a convention, he told a story about the script supervisor yelling at him for adding an “um” to a line. Given his Academy Award-winning stature, John Patrick Shanley scored a clause in his contract forbidding actors from changing so much as a syllable of his work, “um” included. So it might not have been an especially fun time for Bruce, but when Peter Elliot refuses to be bought by shouting, “I’m not a pound of sugar – I’m a primatologist!” it’s hard to imagine anyone who could’ve sold it better.

Congo earned one of its few positive reviews from none other than Roger Ebert. He gave it three stars out of four and provided what might be the last word on how to approach such a singularly fascinating mess:

“False sophisticates will scorn it. Real sophisticates will relish it.”

Congo. Low art. High adventure. You’ll never see another talking ape movie quite like it.

PopHorror Let's Get Scared

PopHorror Let's Get Scared