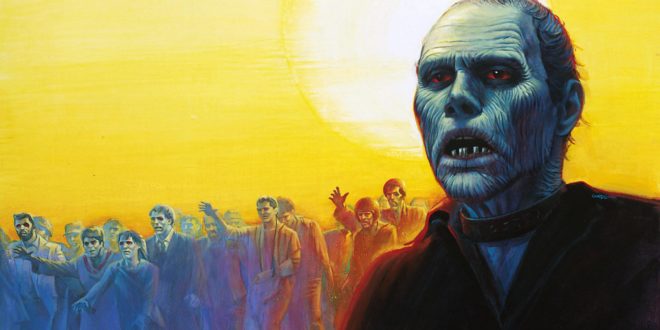

By sheer coincidence, George A. Romero — the iconic horror director — passed away just days before the 32nd anniversary of his classic Day of the Dead. The movie was released on July 19, 1985, and he died on July 16, 2017. Normally, I don’t say much about celebrity deaths, but this coincidence has an eerie ring to it, given the nature of the movie in question. So, for obvious reasons, I especially dedicate this retro review to Mr. Romero.

Assessing The Dead

Like every Romero zombie story, Day of the Dead isn’t just about flesh-eating zombies (or “ghouls,” as they were labelled in Night of the Living Dead.) Instead, this movie is about people, either as individuals or as representatives of the world at large. Romero has said that a number of things in the film were alternately subtle and bold.

In college, movies like this are sometimes called didactic — meaning they are intended to teach, particularly in having moral instruction as an ulterior motive. Some people groan at that sort of thing, but Romero skillfully blended the horror and the lessons together, making them seem organic to the plot, as opposed to having a tacked on feel.

In Day of the Dead, the zombie pandemic has society breaking down, and the faint glimmer of hope lies literally underground in a bunker. This is where mankind has sloppily pooled some resources in a last ditch effort to repair things. Of course, things aren’t really working out down there. The scientists and the military personnel living there struggle to see eye to eye. In fact, they seem to question each other’s merits altogether — both as professionals and as human beings. Too many military men have died gathering zombie specimens for research, and the newly appointed military leader is becoming increasingly despotic. They become liked pissed off little children.

As for the scientist’s team, they are primarily Dr. Sarah Bowman (Lori Cardille), Dr. Matthew “Frankenstein” Logan (Richard Liberty), radio operator Bill McDermott (Jarlath Conroy) and helicopter pilot John (Terry Alexander). Not many people represent the military, either, but the most prominent among them are Captain Rhodes (Joseph Pilato), Pvt. Walter Steel (Gary Howard Klar), Pvt. Miguel Salazar (Anthony Dileo Jr.) and Pvt. Robert Rickles (Ralph Marrero).

Domesticated Zombies?

Romero gathered a great group of actors to cast in Day of the Dead and did an excellent job of exploring both people problems and the idea that zombies could be controlled. It’s a concept that’s controversial to the military, to the scientists, and to zombie genre fans themselves. How could Romero change how we view zombies? They’re not supposed to be anything but killing machines! How could there be a nicer, demonstrably smarter zombie named Bub (Sherman Howard) of all things?

By imposing this question on us (and them), Romero didn’t entirely leave us scratching our heads. Instead, he approached it from at least a quasi-scientific and philosophical perspective. Bub is an example of people being conditioned to behave, for better or for worse. Dr. Logan argues:

“Civility must be rewarded… If it isn’t rewarded, then there’s no use for it. There’s just no use for it at all.”

Elaborating, he says,

“It [The zombie] can be domesticated, Sarah, don’t you see? It can be conditioned to behave the way we want it to behave… They can be tricked into being good little boys and girls, the same way we were tricked into it; on the promise of some reward to come.”

Inarguably, the most heartwarming moments in Day of the Dead happen between Dr. Logan and Bub, as Bub is trained into behaving in a human manner, through the gross yet necessary reward of salvaged human remains (hey, meat is meat, and Bub’s gotta eat!).

In the process, the would-be mechanics of the zombie are partially explained. When they attack humans, it is in fact not for nourishment. They are acting on what Dr. Logan calls “primordial instinct.” While he could just be discussing zombies, it’s useful to treat it also as a metaphor. It’s believable that Romero was hinting at our own instincts toward violence of various kinds.

Sure enough, if you look at the world, you indeed see people becoming violent when they don’t have their way or even when they disagree with each other. When we feel threatened or undermined, we tend to lash out — unless we become domesticated like Bub. Neither path is particularly neat and clean, with each brimming with elements of human folly.

What Do Bub and Dr. Logan Represent?

It seems then that zombies are like a cruel joke, perpetrated by nature and man’s bizarre, destructive fate. They are seemingly of no value, but there are still two basic ways people can react to them. Either they try to eliminate them all systematically (or for sport), or they try to live with them, find use for them, and make them stop trying to eat us.

Dr. Logan represents the compassion that one might feel in this situation, and he symbolizes the necessity of trying to understand. Still, can we try to understand the world without adopting methods that backfire? It seems the answer is a big fat No, both in Day of the Dead and in reality.

Throughout the film, the issue of usefulness is brought up again and again. The notorious Captain Rhodes seems prepared to abandon — or even kill — anyone he no longer finds useful to him. In the process, he foolishly disregards the merits of the research going on, making practically zero effort to understand it — even when the results stare him right in the face with the name Bub. Due to this ignorance and arrogance (and a few tragic accidents), things fall apart. The group makes an already bad experience worse, and a collective mental instability leads to panic and death. Even though there are uproarious gross-out scenes aplenty, Day of the Dead is certainly a thought-provoking and fun movie where examining philosophy is part of the fun. Imagine that!

A Great Quote

Day of the Dead also features one of my favorite quotes from any movie (horror or otherwise) from John the pilot, which sums up a great deal of what’s so nonsensical about the world.

He says in his gentle Jamaican accent,

“We don’t believe in what you’re doing here, Sarah… You know what they keep down here in this cave? Man, they got the books and the records of the top 100 companies. They got the Defense Department budget down here. And they got the negatives for all your favorite movies. They got microfilm with tax return and newspaper stories. They got immigration records, census reports, and they got the accounts of all the wars and plane crashes and volcano eruptions and earthquakes and fires and floods and all the other disasters that interrupted the flow of things in the good ole U.S. of A.

“Now, what does it matter, Sarah darling? All this filing and record keeping? We ever gonna give a shit? We even gonna get a chance to see it all? This is a great, big 14 mile TOMBSTONE! with an epitaph on it that nobody gonna bother to read. Now, here you come. Here you come with a whole new set of charts and graphs and records. What you gonna do? Bury them down here with all the other relics of what… once… was. Let me tell you what else. Yeah, I’m gonna tell you what else. You ain’t never gonna figure it out, just like they never figured out why the stars are where they’re at. It ain’t mankind’s job to figure that stuff out…”

When Sarah says this is all there’s left to do, John disagrees:

“Shame on you. There’s plenty to do… so long as there’s you and me and maybe some other people. We could start over, start fresh, get some babies and teach ’em… never to come over here and dig these records out…”

In Conclusion

Day of the Dead is filled with great moments, performances, concepts, quotes, and memorably gory death scenes. It is, without a doubt, one of Romero’s finest creations. And, in all honesty, I have a hard time disagreeing with John’s sentiments. They simply make sense. Now, if only the rest of the world would understand.

R.I.P George A. Romero.

PopHorror Let's Get Scared

PopHorror Let's Get Scared