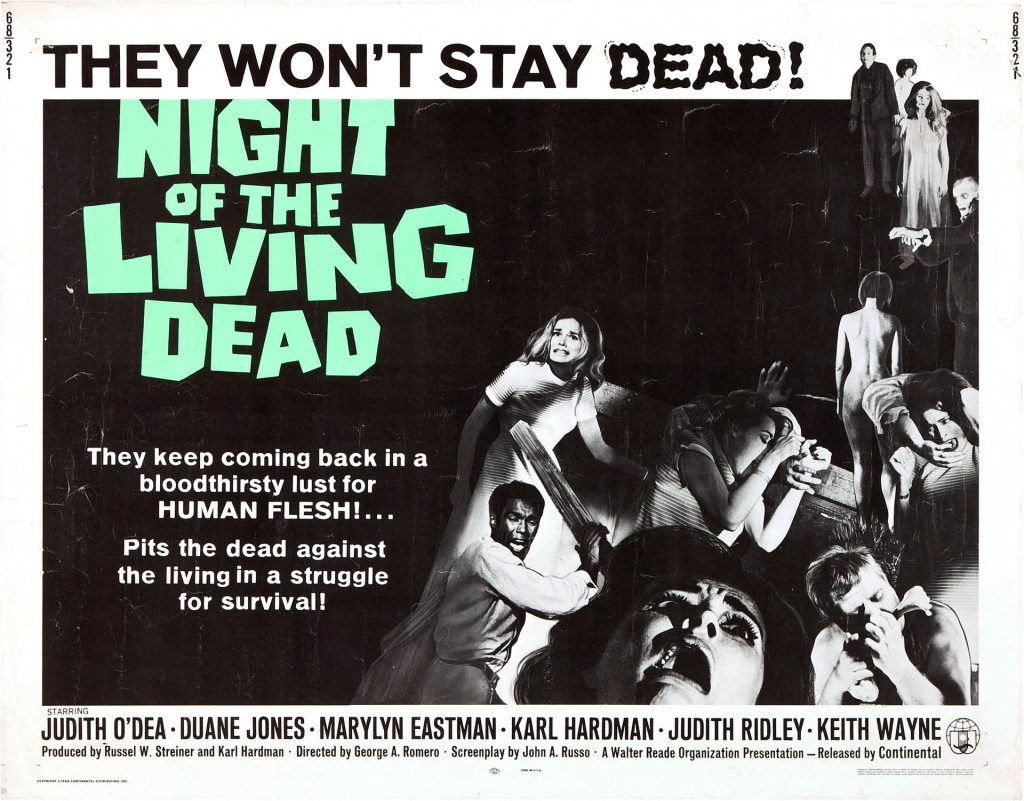

The idea of a horde of undead, flesh-eating ghouls was completely unheard of before George A. Romero picked up a camera in 1967 and filmed one of the most influential horror movies of all time, Night of the Living Dead (1968). Now a pop culture icon, Romero has spent nearly a half-century creating films that explore both social commentary and satire, all the while scaring the bejesus out of us. Although he only has 20 films to his directorial credit, his standout performance in the world of the soulless ghoul and his unique vision to filmmaking make him a standard for all other horror directors to follow. The film is now officially 50 years old. To celebrate this milestone, let’s take a look at his debut and most popular film to date – Night of the Living Dead.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TAGtIQvebs

Tired of filming commercials and bits for the children’s show Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood, Romero and friends John Russo, Marilyn Eastman, Russell Streiner and Karl Hardman decided to capitalize on the current Hollywood trend of bizarre tales by forming the production company, Image Ten, and writing a horror comedy about teenage aliens. Drawing inspiration from Richard Matheson’s book I Am Legend, Russo rewrote the script in a darker, more serious tone, changing the aliens to flesh-eating, reanimated human corpses and creating a three-part story that would go on to become Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985).

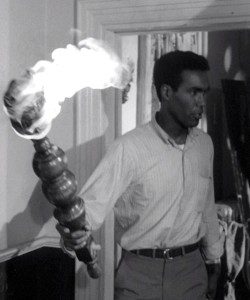

The filmmakers pooled their money and came up with $6,000, which was still about $108,000 short of what they needed to complete the filming. Although they managed to scrape together the rest, every decision was then based on cost with Romero and his crew going to great lengths to pinch pennies, from the use of 35mm black and white film to the local filming locations in Evans City, PA. With no money in the budget for special effects, edible flesh was made up of a roasted ham and offal from one of the actor’s butcher shops and Bosco’s chocolate syrup was used as blood. The zombies themselves started off with simple, white faces and blackened eyes, although later on, chunks of decaying flesh was shown with spackled on mortician’s wax. Although it seemed like a setback at the time, the finished film was all the better for its lack of expensive effects. Film historian Joseph Maddrey calls the black and white filming guerrilla-style, and says it resembles, “the unflinching authority of a wartime newsreel,” adding that these choices make it, “seem as much like a documentary on the loss of social stability as an exploitation film.”

The film itself inspired both criticism and accolades from critics.  While the social taboos of cannibalism and matricide were shocking to some, just as many applauded Romero for his insight and bravery. After catching Night of the Living Dead at a Saturday afternoon matinee, Roger Ebert said,

While the social taboos of cannibalism and matricide were shocking to some, just as many applauded Romero for his insight and bravery. After catching Night of the Living Dead at a Saturday afternoon matinee, Roger Ebert said,

“The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying… It’s hard to remember what sort of effect this movie might have had on you when you were six or seven. But try to remember. At that age, kids take the events on the screen seriously, and they identify fiercely with the hero. When the hero is killed, that’s not an unhappy ending but a tragic one: Nobody got out alive. It’s just over, that’s all.”

Talk about a shocking revelation: the good guy does not always win, the bad guy is not always defeated, and things do not always wrap themselves up with a neat, little bow just as the credits roll. All bets were off. And although Romero denied hiring Duane Jones because he was black, the simple fact that he, as the movie’s well-spoken hero, Ben, is killed not by the undead but by the bullets of a white man’s gun, does more for the social commentary aspect of the times than any spoken word, guilt-ridden soliloquy could ever have hoped to accomplish.

No matter his initial intention in making Night of the Living Dead, George Romero compiled the perfect storm of uncomfortable subjects, social taboos and political unrest that has lasted nearly fifty years and still stands head and shoulders above the rest as one of the scariest films ever made, needling the soft spots of even the most jaded horror fan. Every zombie loving filmmaker since has been inspired at least in part by Romero’s debut film, and the director himself has gone on to be involved in five sequels and three remakes related to the original 1968 film. If a half a century of acknowledgements and thanks from filmmakers all over the world isn’t considered inspiring, then I don’t know what is.

PopHorror Let's Get Scared

PopHorror Let's Get Scared